The Ancient Idea Behind Analytics

University of Tampa, March 2025

You probably don’t realize it, but an obscure 15th-century Italian monk named Luca Pacioli invented the world’s best data strategy, which is still the foundation for analytics today.

Pacioli (who lived with Leonardo DaVinci) invented almost every accounting concept you know, like journal entries, financial statements, and trial balances. His disciples were destined to work in the trades, so Pacioli focused on using math to describe their commercial work. He turned their every activity into data.

As a mathematician, Pacioli understood data as an entire system that reflected what was happening in the business. As a monk, he knew the universe was infinite and there would always be more to learn, so he didn't aim to flatten all the world’s knowledge into data. Instead, he used math and accounting to discover more about the world around him. The accounting concepts he invented haven’t changed in the 600 years since, but they opened the door to a world of business analytics that continues to grow today.

Pacioli cared deeply about data quality. He’s famously quoted as saying, “A person should not go to sleep at night until the debits equal the credits.” Six hundred years later, that’s still great advice.

The Data Bridge

Pacioli built his approach around the two-sided journal entry, known as “double-entry accounting. Behind it lies the idea that your business data describes two things:

What you did and what you have.

That framework leads to two reports: a statement of activity (profit and loss) and a statement of position (balance sheet).

I don’t think I could overstate the importance of this concept, not just for accounting but also for analytics. Double-entry accounting creates a bridge connecting where you started, where you ended, and what happened in between.

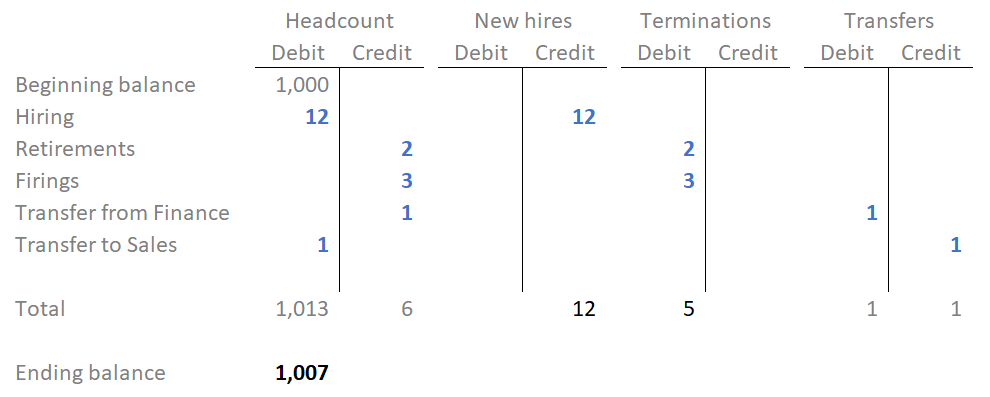

Take your company’s headcount (the number of employees) as an example. At the end of last week, you had 1,000 employees. That’s the starting “balance” of employees. Then, activities happen:

A new employee starts work. That’s a credit to “new hires” and an increase (debit) to headcount.

People retire. That’s a debit to “terminations” and a decrease (credit) to headcount.

You fire some employees. That’s also a debit to terminations and a credit to headcount.

An employee transfers to another department. That’s a decrease (credit) to the first department and an increase (debit) to the second department, with no effect on the total number of employees.

Here’s what that data looks like in Pacioli’s double-entry accounting framework:

Everything that happens to employees increases one account and decreases another. You added 13 employees but lost six. At the end of the period, you have 1,007 employees. You can use this same accounting approach to analyze any asset, like the inventory in your warehouse, the backlog of orders in your sales system, or the number of subscribers to your blog.

Flowing Data

Analysts call this approach “bridging” because it connects data between two points in time. I use the word “flow” to describe it because data constantly moves, and recording it like this allows analysts to answer almost any question straight from the data.

A good data strategy depends far more on how well the data flows than on your ability to write good reports.

Does your data flow? If people feel friction in the data you’re giving them, it’s probably not because you wrote lackluster reports. Instead, the data you’re giving them isn’t naturally connecting points in time together like a journal entry. Double-entry accounting changed the world five centuries ago, but maybe your data platform isn’t using this world-changing solution yet.

But when your data solution bridges the balances like that 15th-century monk taught, data will flow fast, clean, and fresh to all the decision-makers.

Thanks for the history lesson. It looks like a good data strategy can work well with or even sometimes without the advanced technology. As you said. It worked well 500 years ago. Of course, we need the technology to handle the volume of data, but without the correct strategy even technology won't help.

Very interesting! Great history lesson, too!